Earth Day at 50: Environmental Author Discusses Young People's Part in the Continuing Movement

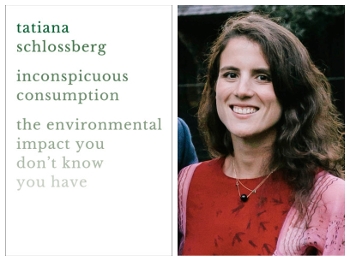

Author and environmental reporter Tatiana Schlossberg discusses what young people should know about climate change, the importance of talking about the issue, and the impact of the novel coronavirus shutdowns.

Most environmentally-minded tweens and teens recoil in horror at the sight of a plastic straw but don’t think twice about the environmental impact of hours of streaming video or theshirt they've just bought. That's not their fault. Not all behaviors that negatively impact the environment get the spotlight.

Most environmentally-minded tweens and teens recoil in horror at the sight of a plastic straw but don’t think twice about the environmental impact of hours of streaming video or theshirt they've just bought. That's not their fault. Not all behaviors that negatively impact the environment get the spotlight.

With that in mind, and the 50th anniversary of Earth Day on April 22, SLJ interviewed Tatiana Schlossberg, author of Inconspicuous Consumption: The Environmental Impact You Don't Know You Have, about what young people should know and how they can make a difference. She discusses the successes of the activists who created Earth Day in 1970, the impact of the novel coronavirus stay-at-home orders, and the importance of voting, having community conversation about climate change, and focusing on action, not guilt. Her insight will give kids—and educators seeking new discussions with students about climate change and Earth Day—some things to consider.

What is are the biggest misconceptions young people have when it comes to the environment?

Young people seem to understand that we are dealing with structural and systemic problems and should be trying to address them that way, not only thinking about our plastic straws and our fast fashion habits. Despite that knowledge, I still get the sense that people my age and younger tend to take for granted simpler environmental successes that don’t immediately appear to have a lot to do with climate change—things like clean air and clean water. Until the 1970s, the U.S. had barely any environmental laws regulating pollution, preventing companies from dumping waste into our drinking water or pumping hazardous materials into the air. It is because of the young environmental activists in the early 1970s that most of those dangerous practices were stopped.

These activists organized the first Earth Day 50 years ago, bringing 20 million Americans to the streets, and in the 1972 midterm elections, worked to defeat the 12 members of Congress with the worst environmental records. They beat seven of them, and without that change to Congress, we probably wouldn’t have the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Endangered Species Act, and more. I think it’s easy to think that regulations don’t have a lot to do with our everyday lives, but they do. Of course, these regulations are flawed—millions of Americans are exposed to dangerous pollutants every day, and they are disproportionately communities of color or low-income communities. But we don’t get clean air and clean water by accident. We have to make sure that these basic necessities are a guaranteed right for every American.

What behaviors take a toll on the environment that young people would be shocked to know?

When I was writing my book, which is about the hidden or unexpected environmental and climate impacts of a lot of our stuff in four areas—the internet and technology, food, fashion, and fuel—I was really surprised to learn about the impacts of the fashion industry. I probably shouldn’t have been since clothing and textiles drove the Industrial Revolution and have been the engine of globalization in the last couple of decades. The clothing industry connects consumers to people all over the world who make our clothes; we are all connected by many of the climate and environmental impacts that result from wasteful and polluting practices. I think maybe some of us have heard about fast fashion and how wasteful it is—that the average item of clothing is only worn seven times before being thrown away, but there was so much more than that. One example: It takes about 2,500 gallons of water to grow about two pounds of cotton, and cotton is often grown in places without a lot of water to begin with. To turn some of that cotton into a pair of jeans can use as much as an additional 2,900 gallons. As consumers, we never hear about that.

|

Photo by Elizabeth Cecil |

What tween/teen behavior change could have the most impact?

Usually, I say that the most important action any of us can take is to vote in every election, and for young people who are 18 or turning 18 before the next election, that’s definitely true. I know that can be frustrating and feel really unfair for those who care a lot about these issues and feel like you don’t have a voice. But I think there are still other things you can do: You can make sure all of the adults in your life are registered to vote, and actually vote. You can volunteer for candidates who you think share your values when it comes to climate change policy.

I also say that the second most important thing to do is to not support companies that aren’t transparent about their practices, at the very least. But I know that young people aren’t always in charge of deciding what to buy—what to eat or wear or how to get around. But almost every company is going to be competing for your business since you’ll be the next generation of consumers. You can use that power to your advantage—to demand transparency, and then to demand they do better.

What actions within schools and local communities would make the biggest difference?

It might be hard to believe, but only about a third of Americans say they talk about climate change at all. Once they do, though, they are more willing to consider it a risk and to support policies to mitigate it. So talking about climate change at school and at home is really important, and you are probably some of the best messengers we have for climate action.

Does every little bit actually help?

Well, it’s complicated. Yes, every little bit helps, and I think it’s important, if you care about this issue, to live in line with your values, and to act on new information as you learn it. But I think the narrative of personal responsibility when it comes to climate change has actually been pretty destructive: It makes us feel guilty for things we didn’t know about or have no control over, and it lets those who are really responsible—fossil fuel companies and the politicians who protect them—off the hook. I don’t think we should feel individually guilty for climate change; I think we should feel collectively responsible for building a better world together. And the best way to do that is to make structural changes to the way our economy and government works, and the best way to do that is by working together, just like those environmental activists did 50 years ago.

Finally, what impact have the stay-at-home orders had on the environment and could it have a long-term impact?

It’s probably too early to say anything definitive about the long-term effects of the shelter-in-place orders on climate change. Emissions certainly have gone down from less traveling, less industrial activity and less electricity usage overall, and the air quality is better in places like Los Angeles and parts of India and China, too. I worry that people will take this to mean that the best way to “solve” climate change will be a complete economic shutdown in which millions of people lose their jobs. Really, what we need is to use this as an opportunity to invest in clean energy infrastructure and other technology that will help us get to a low-carbon future like the government did in the 2009 stimulus package.

We are also seeing that the closing of schools, food processing companies, and restaurants means that there are a lot of crops going to waste. Food waste is responsible for a huge amount of greenhouse gas emissions, and this year we will certainly see more.

The other negative effects are that the Trump administration is using this difficult economic time to make life easier for polluters, easing restrictions on releasing dangerous pollutants to the air and water, and declining to make standards stricter for an air pollutant called PM 2.5. Exposure to this pollutant—non-white communities are disproportionately exposed—makes people more susceptible to the [novel] coronavirus.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!